By 1944 CE Japan's strategic position was rapidly crumbling.

Its naval supply lines were strangled and its armed forces were obliged to retreat on all fronts.

The navy and air force had lost many airplanes and especially experienced pilots, giving the USA increasing air superiority.

In response, in the autumn of that year some pilots came up with the tactic of deliberately crashing their airplanes into enemy targets, especially ships.

The Japanese high command picked up the idea and created some dedicated suicide units that quickly became known to the allies as "kamikaze", divine wind,

echoing back to the double wrecking of Mongolian-Korean invasion fleets in the 13th century CE by heavy storms.

A suicidal kamikaze attack, launched when other attempts to stop the enemy had failed, appealed strongly to the simplified bushido code that had been hammered into the Japanese military.

Many pilots volunteered, believing that their sacrifice would save the honor of their family, friends and emperor and maybe shield their families from expected atrocities by the Americans.

But the enthusiasm for kamikaze duty was overstated by contemporary Japanese propaganda.

Most pilots, especially in the later stages of the kamikaze attacks, were not volunteers but conscripts, about 1/4 of them university students who were drafted into service.

All kamikaze pilots were relentlessly indoctrinated, drilled and beaten into a single-minded death focus.

The military cleverly fused heroism, patriotism and spirituality into one.

Before pilots took off, they shared a ceremonial draught of sake or water.

Many carried poems, prayers and traditional swords with them.

Even many of those who, after all the coercion, were not convinced of the need to sacrifice themselves did join anyway,

out of comradeship and/or fear for the honor and fate of their families.

Militarily, kamikaze aircraft were effectively guided bombs, steered by pilots instead of gyroscopes or other navigation devices.

At a time when missiles were all unguided, this meant a great improvement in accuracy and efficiency, though at a terrible cost of lives.

The pilots flew a variety of fighters and dive bombers, converted to suicide aircraft.

They also used aircraft built specifically for that purpose, like the rocket-powered Okha.

When Japan ran out of normal aircraft, slower trainer aircraft were used that had wooden frames, which were hard to detect by radar.

The aircraft were loaded with a maximum amount of fuel and typically attacked in groups of 3 - 4 plus a pair of escort fighters.

Some tried to 'skim the waves', flying in low, others attacked from high altitude;

a third method was to combine these two by approaching low and then climb and dive onto the target.

Not just aircraft were used in kamikaze attacks; also mini-submarines, torpedoes, speed boats and divers,

though most were experimental and did not see action because the war ended before they could be used.

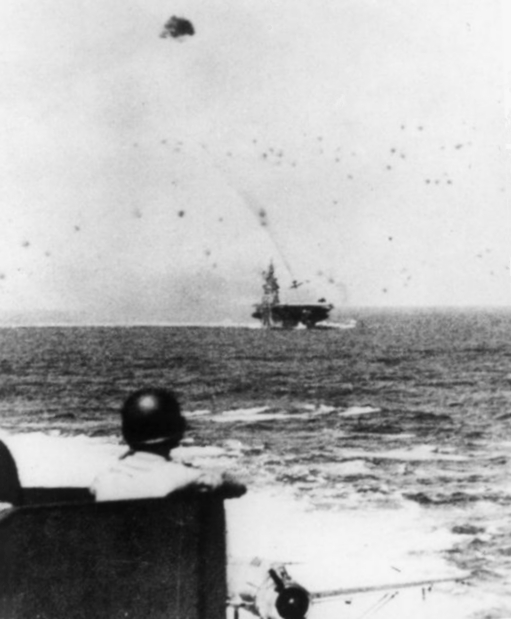

The first organized kamikaze attacks were launched during the Battle of the Leyte Gulf.

In one day 55 fighters managed to sink 5 ships, heavily damage 23 and moderately damage 12 more.

Over the following months many more kamikaze attacks were launched.

These were not so successful as the first, because they lacked well trained pilots and the American navy quickly bolstered its air defense.

Small ships acted as screens for capital ships; more combat air patrols were flown; training was stepped up; ships were equipped with light, flexible anti-air guns.

Kamikazes were also used in the Battle of Iwo Jima.

The last and most intense kamikaze attacks took place during the Battle of Okinawa in 1945 CE, during which 1,465 airplanes sunk or disabled 30 warships and 3 merchant vessels.

British warships, which had armored decks, proved far more resilient than American carriers with wooden decks, though American damage control was very good.

Despite the gruesome toll on the pilots, kamikaze attacks were militarily effective for the depleted Japanese forces.

In conventional, non-suicide naval attacks, battle rates were 60% shot down by combat air patrols; 14% downed by anti-aircraft guns; 22% target misses and 4% hits.

For kamikaze attacks the numbers were 60%, 20%, 5% and 15% respectively.

Also the fuel-stuffed kamikaze airplanes did more damage than ordinary bombs and torpedoes, all in all making them several times more effective.

At the end of the war the Japanese air force had launched almost 1,400 kamikaze attacks and the navy more than 2,500.

The total damage that they inflicted is not very clear.

The best estimates are around 450 - 500 ships hit; 30 sunk, though not a single aircraft carrier;

5,000 allied servicemen killed and an equal number wounded.

Despite being large, these numbers were not enough to turn the odds back into Japan's favor.

The fact that the Japanese knew this, but still persisted in suicide attacks,

shows how far the the idea of an honorable death had become obsessive to Showa Japan.

War Matrix - Kamikaze fighters

World Wars 1914 CE - 1945 CE, Armies and troops